Main Navigation

Altitude sickness is the effect that walking to high altitudes can have on the body in the form of hypoxia (insufficient oxygen to the blood, brain or tissue, and/or the build-up of fluid on the lungs or brain), cold and dehydration. If it does not clear, walk to a lower altitude. Keep warm. Drink plenty of liquids whilst hiking – and avoid alcohol.

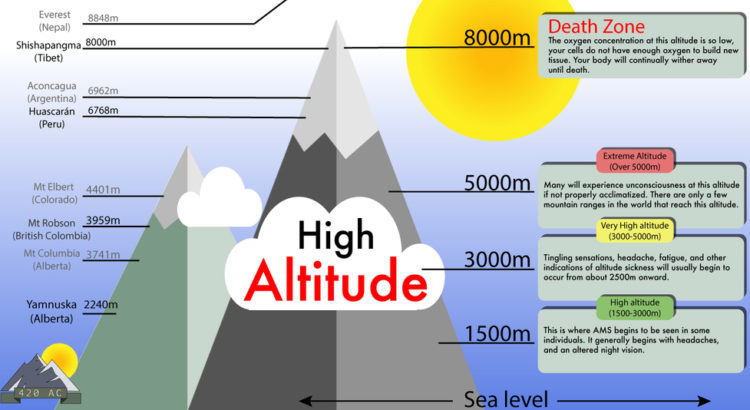

Dry air contains 20.9% oxygen. As you climb to higher altitudes, air density decreases (air “expands” as atmospheric pressure decreases due to the decrease in the volume of earth’s air above you). Consequently the percentage of inspired oxygen in the lungs decreases: at 5 500m it is only 50% of that at sea-level (30% at Everest’s summit).

Generally the body can adjust to these changes – but you need to assist the process and consciously help your body to adapt. The effects of increasing altitude (and the possible onset of altitude sickness) frequently begin to be felt above 2 500m. From 3 000m the guideline is not to rise more than 300m a day and if possible “climb high and sleep low”.

Acclimatization is cumulative and frequently trekkers who feel fit and walk fast on the initial days suffer the most when higher up. Trekking from the start at a slow steady pace helps the body to adjust and greatly reduces the chances of later problems.

(This is particularly important for treks that begin at high altitudes: Everest treks from Lukla start at 2 600m). A rest day on reaching 3 000m and 4 000m is advised. [LDT builds rest days into treks.]

Acute (mild) mountain sickness (AMS) is recognized by the onset of one or more of: headaches, dizziness, fatigue, shortness of breath, loss of appetite/stomach aches and difficulty sleeping. You may feel worse at night when breathing rates generally decrease.

Treatment for AMS

The use of headache tablets and the diuretic Diamox (increases breathing rate and helps remove fluids) frequently sooths or solves the problem.

If symptoms remain severe, descend at least 200m and rest. Drop further if need be. [Start taking Diamox a day or two before reaching 3 000m]

High- altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPE) is a dangerous build-up of fluid in the lung’s air pockets: this prevents the absorption of air and distribution of oxygen to the body.

Symptoms usually develop after two or three days at altitude and include excessive breathlessness (even at rest) and a higher heart rate compared to fellow hikers. You may cough, show white or pink sputum, blue lips.

Treatment for HAPE

Evacuate to a lower altitude for additional oxygen and air pressure. Visit the medical center for the treatment. HAPE can prove to be fatal in hours.

High altitude cerebral oedema (HACE) is a dangerous build up of fluid in the brain recognized by symptoms irrational behaviour, confusion, an inability to walk on a straight line, severe headaches, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, and ultimately coma.

Treatment for HACE

Supply oxygen or carry the patient rapidly to a lower altitude. HACE can prove to be fatal in hours.

HAPE and HACE can occur together. Either condition affects ~ 1% of trekkers between 4,000m – 5,000m. If you did not suffer from AMS on a previous trekking trip, it does not mean that you won’t be affected on your next trek.

Be aware of what your body is saying to you – and inform your guide and fellow trekkers of any irregular feelings.

Good health, a great trek and happy memories are more important than a “macho attitude” – and the possibility of fatal consequences.